Coming Attractions

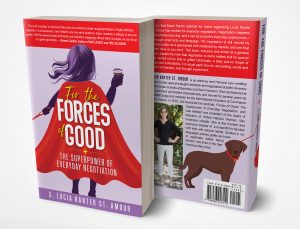

My blog has gone quiet lately because I’ve been so busy with my podcast, and bringing my truly sui generis book to the market (public release date 10/01/22 and sneak peek here)

My blog has gone quiet lately because I’ve been so busy with my podcast, and bringing my truly sui generis book to the market (public release date 10/01/22 and sneak peek here)

Negotiation and the Myth of Rationality (24 minutes to listen)

Language and Negotiation (26 minutes to listen)

Questioning Part 2: A Demo (24 minutes to listen)

The Use of Questions in Negotiation: Part 1 (21 minutes to listen)

A Conversation with Lily Din (19 minutes to listen)

The Marketplace of Ideas: Negotiating Civil Discourse (7 minutes to listen)

Storytelling in Negotiation (22 minutes to listen)

Tammy Kim of The New Yorker described it as “potentially one of the biggest labor victories since the 1930’s.” She was talking about the historic JFK8 Amazon workers vote to unionize on April 1st of this year, 2022.

Tammy Kim of The New Yorker described it as “potentially one of the biggest labor victories since the 1930’s.” She was talking about the historic JFK8 Amazon workers vote to unionize on April 1st of this year, 2022.

First a quick note to say that this is neither an indictment of Amazon as a company nor an endorsement of unions in general. But as an attorney who specialized in labor and employment law and a negotiation expert, I can hardly resist commenting on and analyzing a historic labor negotiation that has unfolded before our very eyes – the first for Amazon outside of Europe, and one that is totally independent / unaffiliated with a national union.

Chris Smalls, former rapper and Amazon warehouse worker, was the trailblazer. How did he do it going up against the country’s second largest employer? A company that spent a budget of $4.3 million on its ant-union consultants last year compared to the JFK8 warehouse budget of $120,000; and after an effort to unionize the Amazon workers in Bessemer, Alabama failed just last year? And not just in Bessemer. Since the nineteen-nineties, several well-established unions have tried and failed to organize at Amazon: the Communications Workers of America, the Teamsters, United Food and Commercial Workers, and the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers.

And what does a historic, national, labor event like this have to do with you and everyday negotiation (setting aside the obvious for a moment, which is an assumption that many of us avail ourselves of Amazon shopping and quick fulfillment of orders)?

Well, let’s examine a few elements of how Mr. Smalls accomplished something so monumental – using strategies that we have already discussed in previous blogs:

First, for our podcast listeners (Pactum Factum: The Superpower Of Everyday Negotiation), recall the chocolate negotiations from Episode 2 and round 3: asymmetry. In the JFK8 Amazon union drive, we have classic asymmetry in power, in precedent, and financial resources.

So, Smalls started with FRIENDS. He and a few other co-workers had been fired from the JFK8 fulfillment center on Staten Island after the first Covid breakout, allegedly due to failure to observe social distancing rules. By partnering with a good friends who were similarly situated to Smalls (having been terminated or disciplined by Amazon), Smalls may have started small, but he started smart by finding allies. Namely: Derrick Palmer, Jordan Flowers, and Gerald Bryson.

Second, I direct you to Episode 3 and my admonition to never underestimate anyone. Amazon’s chief counsel made the mistake of describing Mr. Smalls as “not smart, or articulate,” in an email mistakenly sent to more than 1,000 people. This backfired big time and contributed to Smalls rising to be the very “face” of the organizing effort.

Third, Smalls made it easy on people. He went to them. He and his cohorts met workers at bus stops, the ferry stop and outside the warehouse

Fourth (and this really should be first, also harkening back to Episode 2 and previous blogs): rapport, rapport, rapport! He started with small gatherings, bonfires, brought homemade baked Ziti (that’s a type of pasta). Sidenote: the breaking of bread is actually incredibly important in negotiation because it generates group oxytocin, which is the bonding hormone.

5th: empathy and relationships. Also in Episode 2, we discussed analyzing which of the Richard Shell categories of negotiation yours falls into. This one was heavy in the relationship category. Smalls and fellow organizers worked from within the organization. One of the main reasons the Bessemer effort failed is because it was an effort from the outside by a large labor union. The workers felt like the union didn’t know or understand them. Smalls focused on bonding and relationships.

6th: LISTENING (Episode 7 and Episode 8). Frustrated warehouse workers were worried about safety, rising infection rates of Covid, and other working conditions including bathroom breaks. They felt that the company ignored their concerns. Smalls and his team listened to them as well as reasons why some workers didn’t trust unions from a previous job, which earned them trust and validity for the cause.

7th: they PLANNED. They analyzed the parties / the players. They set up a GoFundMe campaign; visited the Bessemer warehouse to learn from the 2021 union drive; interviewed other previous organizers; examined past practice and how to challenge standards and norms that Amazon had utilized as its past playbook. They even leveraged third parties as a voice of authority and validity: that is, A coalition of New York City officials and residents who chased out Amazon in 2019, when the company tried to install a secondary headquarters in Queens and avail itself of more than three billion dollars in public subsidies; and in 2021, the state’s attorney general lawsuit against Amazon over health and safety violations. Contrast this to Alabama Senator Tommy Tuberville’s expressing his distaste for the Bessemer union.

They set high, specific, justifiable goals (also Episode 3): for example, the labor board requires 30% of the eligible workforce to sign cards to authorize a union, and they set a goal of 40%.

Organizers put in the TIME to research and analyze INTERESTS (again, Episode 3): they made thousands of phone calls. Immigrant members of the organizing effort used WhatsApp to garner support in French, Arabic, and Spanish.

And then, they initially failed. The labor board rejected the initial application as failing to demonstrate sufficient signatures – due to payroll data submitted by Amazon that called into question the validity of some of the signatures that had signed cards.

So they continued building rapport and making it easy for workers to get informed and join the movement: with TikTok videos, s’mores and get-togethers complete with Marvin Gaye music. And more empathy (never gets old!) – including setting up a funding campaign for a fired Amazon worker who became homeless.

They also lawyered up, joining with an attorney who represented the organizers free of charge.

The result was no slam dunk. Many Amazon workers were satisfied with Amazon, grateful for the hourly wage and the benefits, fine with the status quo or suspicious of unions and/or not wanting to pay union dues. The final tally was 2,654 in favor to 2,131 against unionizing.

But just look at how starting slowly, using empathy, planning, listening, rapport, assessing power v. leverage, researching standards and how to challenge them – steadily flourished to make a large scale difference. That’s why the small stuff matters. If you commit to these habits in little ways with your communication and actions everyday, it all adds up.

By Lucia Kanter St. Amour, Pactum Factum Principal